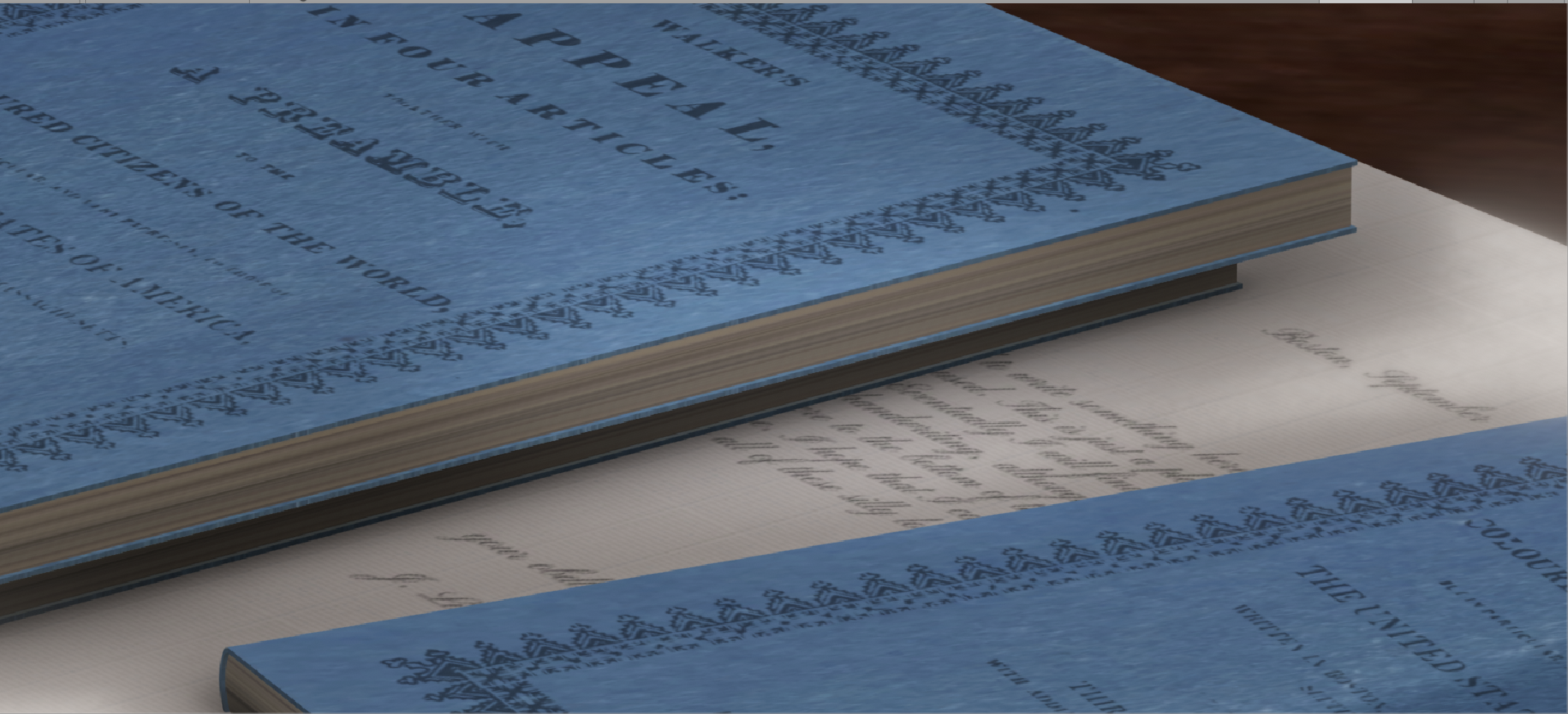

For the past semester, we’ve been working on recreating the home and surroundings of David Walker, a prominent Black abolitionist based in Boston in the late 1820s. This project initially caught my interest because it was a focused study of Black history in Boston, specifically about a prominent Black historical figure that I wasn’t previously aware of. Furthermore, the 3D aspect of the project wasn’t something I had done and knew nothing about. I have always been interested in how urban landscapes affect history and policy, so I was excited to learn more about 3D modeling and how it can add to our understanding of historical events. As a Black student, I was anxious to know about the Black community around me. Helping to visually represent part of its history was a great place to start. Reading David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, appreciating what an important role it played in Black liberation (amongst his other contributions), and then attempting to get to know Walker himself has been an illuminating process thus far.

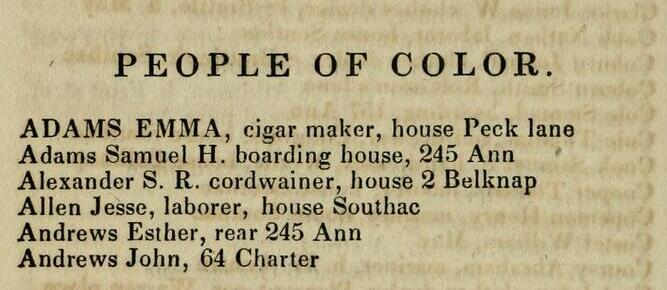

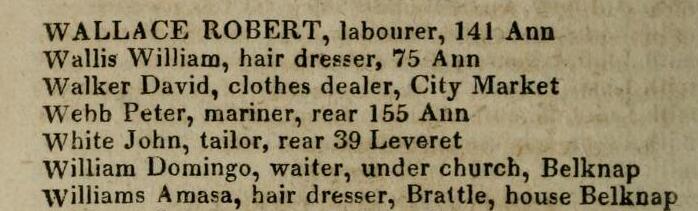

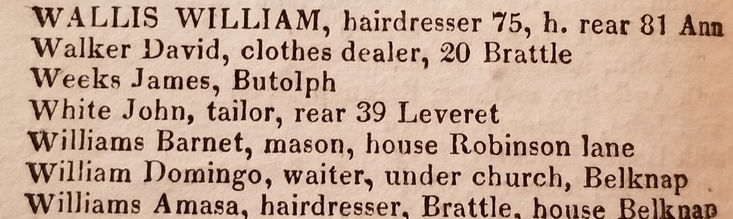

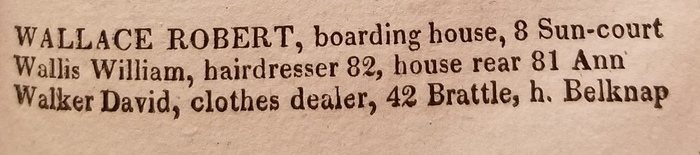

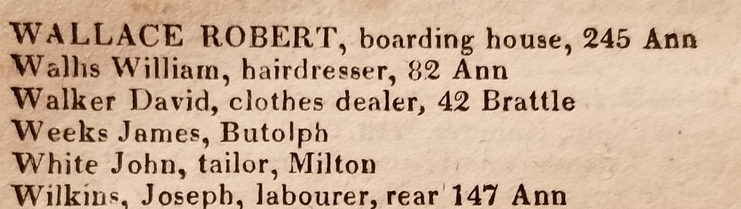

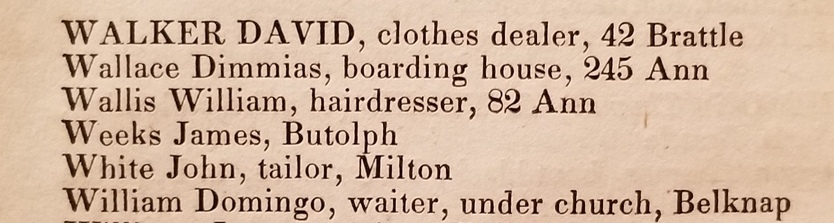

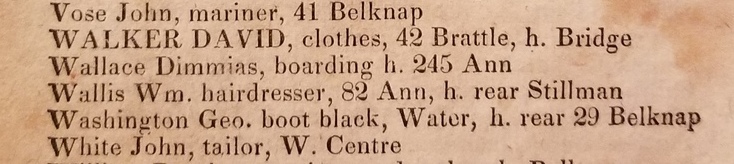

What surprised me most about this project was how much historical and archival research differs from most of that done in the social sciences. As a social science student I went in with the expectation that the research work would be easier, or at least different, from what it turned out to be. I had never looked through anything similar to city directories, censuses, tax and land records, or birth and death certificates. At first, it was admittedly frustrating how long it could take to scour through sources like this and usually reach a dead end. It was also harder to find sources; Since I started college in the pandemic, I had never even taken a book out of the library, let alone requested access to digital resources from archives, collections, and libraries across the US. As the project went on, I got better at knowing what to look for in historical documents and how to access what I needed. More importantly, I became more patient! The research aspect of the project is now my favorite, and easily the most rewarding. On a surface level, it feels good to make a breakthrough or find the perfect document, but on a deeper level, it is rewarding to uncover more about David Walker, Eliza Butler, and the Black community of the 1820s. There is so much I didn’t know about this moment in time. Even more surprisingly, a lot about the early 1800s is hard to pin down. Even the most basic details of a figure like David Walker’s life, like his birth date and town, are cloudy. Obviously, Walker’s race contributes to this. For me, it really puts into perspective how record keeping has changed overtime and how difficult it is to understand a person of the past.

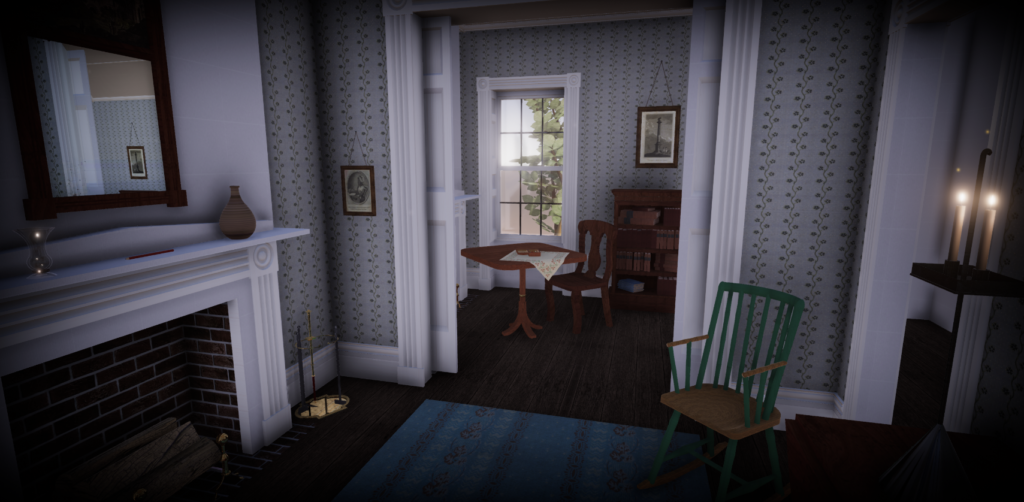

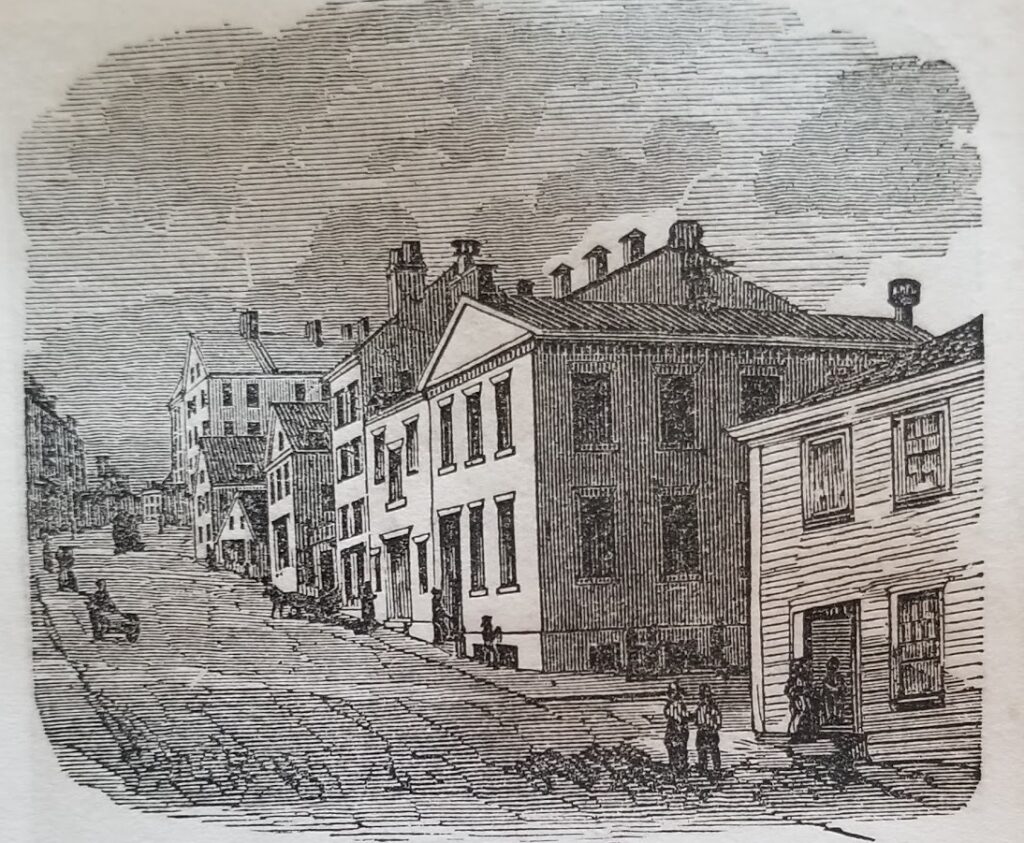

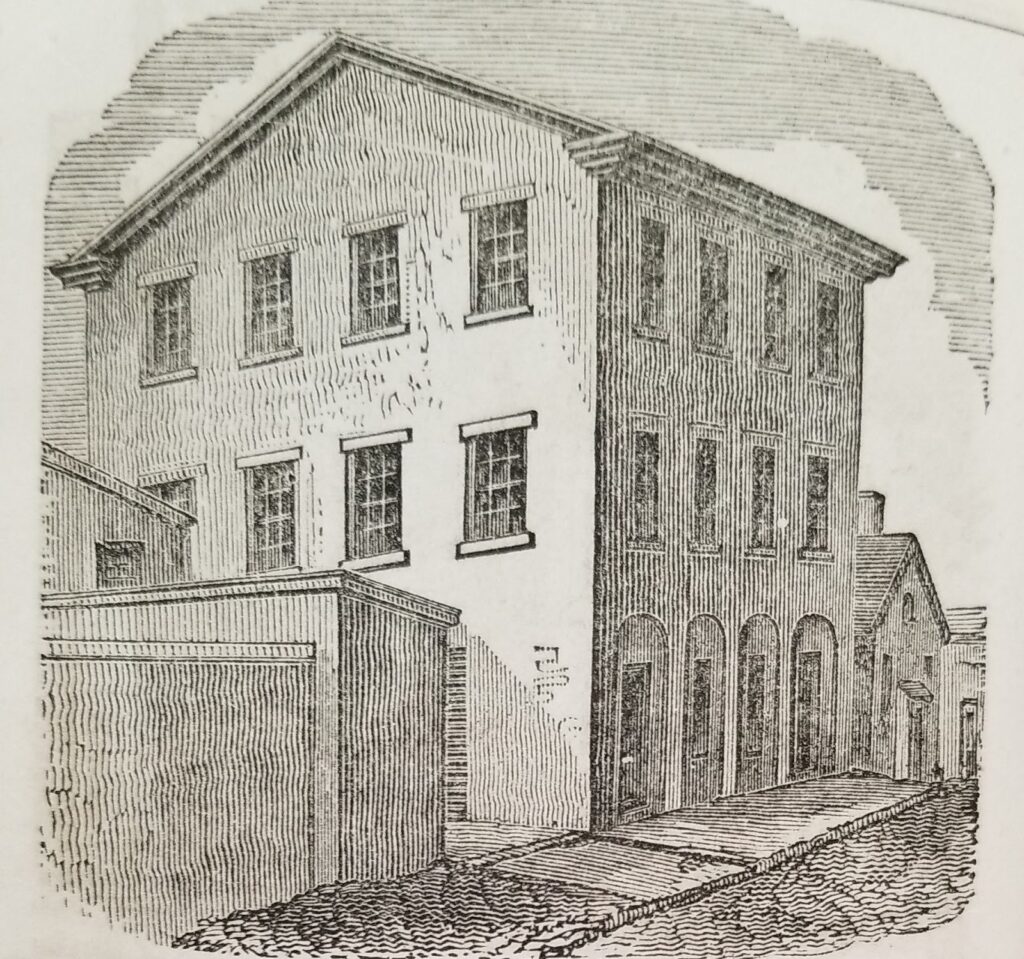

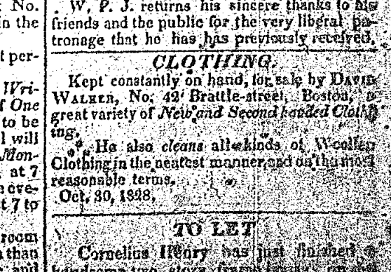

I also realized how much technology can help people understand different periods of time. As the majority of the project focuses on 8 Belknap St. (now 81 Joy St), Walker’s personal home, we’ve had to spend a lot of time considering what Walker may even own. With no pictures or detailed writings about the house, a lot of the information has to come from community members, newspapers, ads, tax/legal records, or other similar sources. While Walker’s writing, city and state records, historical documents, and research papers can help someone understand what Walker contributed to his community and Black liberation, understanding the physical space Walker operated in helps to understand David Walker himself. Not only as an accomplished Black author and passionate abolitionist, but as a father, a husband, a store owner, a newspaper contributor, and person. 3D modeling adds a depth of understanding to historical scholarship that more “traditional” research methods cannot as easily capture. Recreating communities like that of 1820s Beacon Hill allows us to understand what living in these spaces was really like, going beyond what they contributed to history or what patterns can be observed in them. It’s exciting to know that projects like these are becoming more and more common so that historical scholarship can create increasingly human understandings of the past.

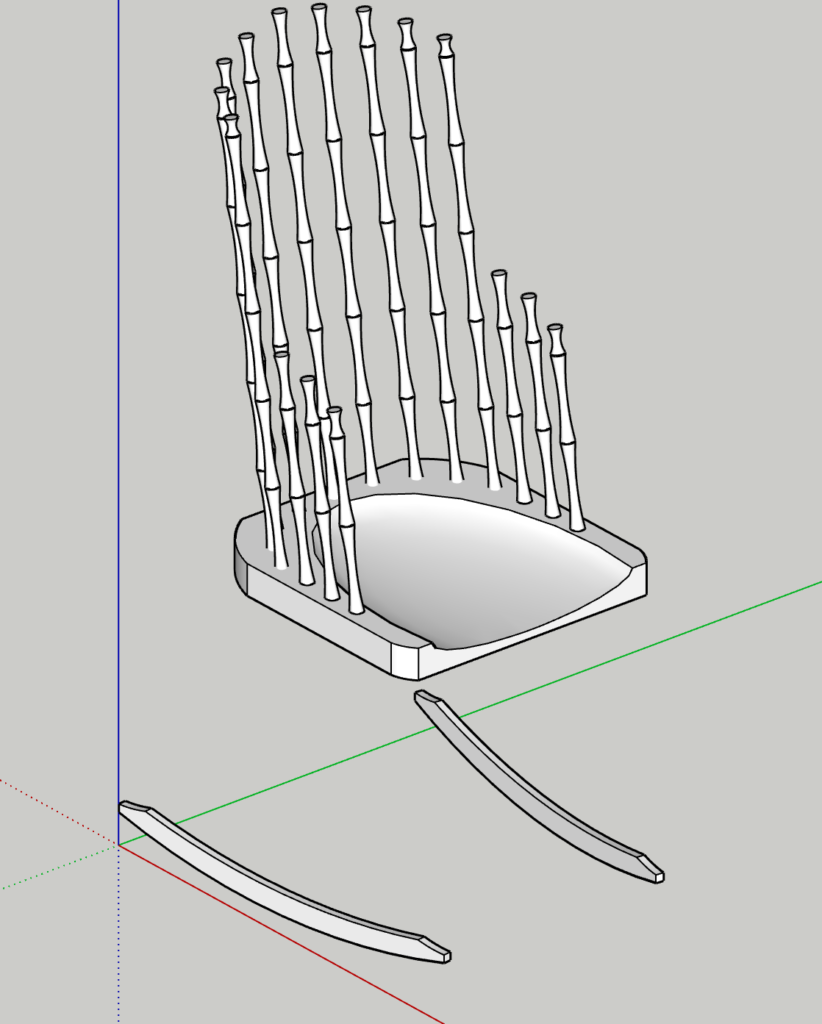

That being said, 3D Modeling was another personal learning curve. I have never worked with any sort of 3D technology prior to this project. But once again, I gained an appreciation for the 3D modeling process, both in Unity and Google SketchUp, two of the programs we are using to recreate Walker’s space. I’m not a particularly math or computer-minded person, so this part of the project is still the hardest for me. Because of that, I’m very happy to be learning these skills early on, and in a group setting. Watching how Professor Linker, Liam, and my peers approach 3D spaces and geometry has been invaluable. In most cases, they see patterns that I don’t while creating a 3D object. Over time, this has helped me improve my modeling skills, but also how I visualize 3D objects and spaces. I’m looking forward to modeling more objects on my own, even though I still think it’s a weak spot for me. Practice makes perfect!

The first object I made is a sad iron, pictured below. The object was more difficult than I thought it would be to make. The curvature of the handle was the most difficult part to visualize. I still want to go back and try to smooth the edges of the iron a bit. The scale was also difficult, since I had to make the object at a 10x scale to be able to work at the detail level I needed. Still, it was my first digital project on my own, and I was able to get a pretty close replica to a Sad Iron of the time.

I look forward to texturing the model later on to add age and wear. I am now working on a rocking chair, which is a lot more complicated, but I have a better grasp on how geometry and 3D space work and I’m more comfortable experimenting with SketchUp. It took a lot more research to figure out the dimensions of the rocking chair, since it is a complex piece of furniture in real life as well, so it’s taking more time on both ends. That model as of today is pictured below. Other than that, we’ve been working on trying to piece together Eliza Walker’s life, as she’s an important part of Beacon Hill as well.

Over the past semester, I’ve learned a lot more about academic research and how technology and the humanities can intersect. I’m excited to see the rest of the project develop and keep working on research and modeling skills.